"Vibecode NetBird in a weekend and take 5% of the company." — Misha, CEO of NetBird

Before that becomes a headline, let me tell you how we got here.

The Hardware Beginning

NetBird didn't start as a company. Not even as a network security project.

It started as a side hardware project in my apartment in Berlin in mid 2020.

At first, I just wanted a privacy-first Dropbox alternative, something anyone could use to store their personal data at home and access it from anywhere, connecting directly to their home network.

Of course, you might ask: why reinvent the wheel? Just get a Synology NAS and use a VPN. But that's not easy for non-technical users. And honestly, I wanted to reinvent the wheel. Why not build a better one? With privacy in mind — meaning no provider could see my traffic. Something so easy to set up that even my mom could use it.

At the same time, Google had just killed free Photos for Android , and suddenly everyone was talking about owning their own data again.

Then Raspberry Pi dropped the Compute Module 4 (CM4) with native storage capabilities, and it felt like the perfect moment, a chance to build something new for the homelab community (and all non-technical moms in the world?).

I pitched this idea to Maycon, a friend of mine—the kind of infra guy who scrolls through tcpdumps instead of TikToks.

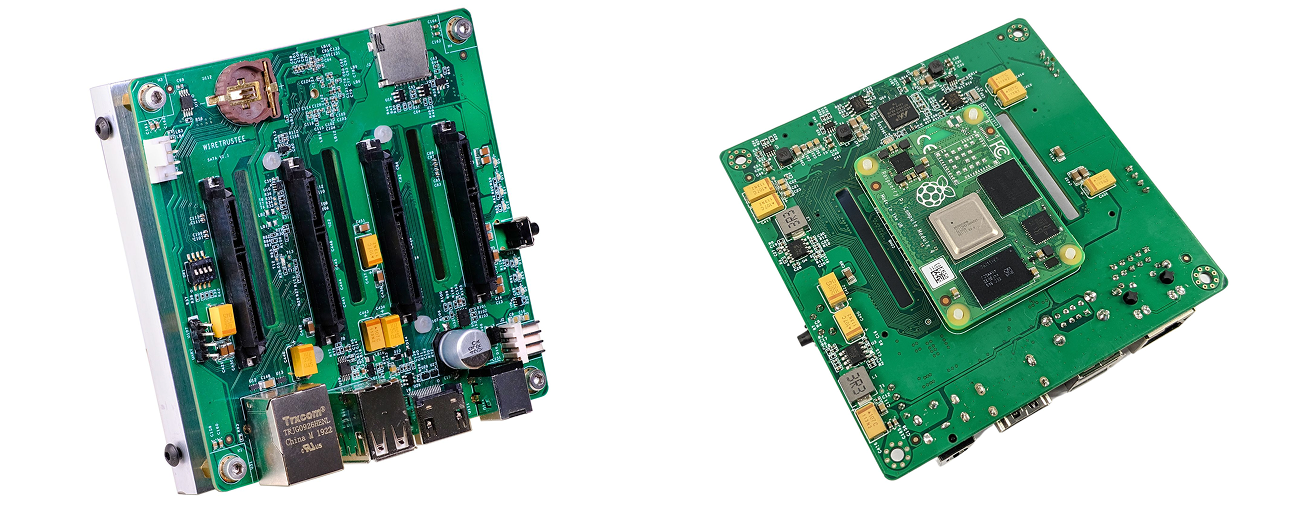

So we started hacking, building a Raspberry Pi–based NAS. A Pi carrier board powered by CM4. "You became a hardware designer," Maycon joked at one point, watching me moving tracks in KiCAD and ordering PCBs in China.

Hardware is hard, and I gotta say — that was my first hardware project of such complexity. I'm honestly a terrible hardware designer. As a software engineer, I'm used to moving tracks (lines of code) on my screen, not on a PCB. There was a temptation to give up and use something already built. A few alternatives were explored, like ODROID-HC4. But that excitement to build the first native Raspberry Pi NAS was stronger. And we wanted a 4-bay NAS, not less!

After a couple of months of prototyping and a few thousand dollars spent on external help with the board design, the prototype was ready. Look at this beauty!

Of course, any DIY NAS is incomplete without a full-blown acrylic case. I spent countless hours designing this one too — in two variants, by the way: one for SSDs and one for hard drives. The final kit looked like this:

After a few months of hard work, the RPi project was complete.

This whole thing went viral, thanks to a Reddit post and Jeff Geerling (if you know Raspberry Pi, you must know him too). The assumption was correct: "people will be excited about the first Raspberry Pi NAS." That was the first time I experienced the power of community and word of mouth. Unsurprisingly, we used the same approach for NetBird.

Wait a minute! After reading all of this, you're probably asking: "NetBird is a software company doing networking. How on earth is this RPi NAS related to networking?" Here's the second story that happened in parallel.

The Software Beginning

Remember when I mentioned privacy, VPN, and direct connection to the NAS? The second critical part beside hardware was software — specifically, the connectivity layer that would let users connect to their NAS from anywhere. The requirement was simple: the connection had to be direct (peer-to-peer) and encrypted (also peer-to-peer).

Given our P2P requirement, we had to come up with a smart, easy-to-use networking layer. So what were the options? Not many, really. Either develop our own protocol or choose an existing one. Here, we didn't reinvent the wheel.

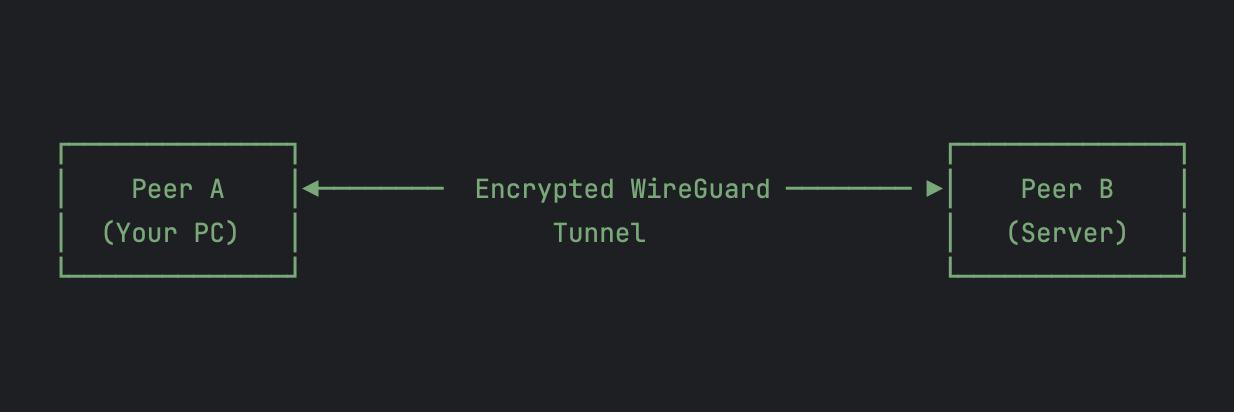

Maycon had a brilliant idea: use WireGuard. Before that, we were actually considering OpenVPN since I'd used it in other projects, but after Maycon's WireGuard pitch, the choice was obvious. Its peer-to-peer nature was a perfect fit for our project. It's lightweight, secure (P2P encryption), easy to configure, and it was very popular at that time (and still is).

We also had a few discussions about what programming language to choose: Rust, Go, or C++? We weren't too familiar with any of them (I personally come from a Java background), but Go seemed the most promising and exciting. Well, and for a software engineer programming language is just a tool, right? Go was also Maycon's pitch, by the way. Plus, there was a userspace implementation of the WireGuard protocol — wireguard-go . So the choice was made: Go.

The NAT

The next step was to make the system simple enough that it just worked. WireGuard is elegant and lightweight, but it still requires real configuration: managing keys, defining peers, and, most importantly, figuring out how machines find and reach each other. Without solving that, everything else falls apart. Maycon kept stressing that it should work without anyone having to think about their home routers — it had to be plug-and-play so we could reach more than just tech-savvy users. That idea has guided us ever since.

What we needed was a mechanism that could handle discovery and setup, then get out of the way once a direct peer-to-peer connection was established. That problem leads straight into the world of Network Address Translation (NAT), a technique developed to fight IPv4 address shortage.

This period was all about punching holes in firewalls, and Maycon's skills scrolling through tcpdumps came in very handy. Well, UDP dumps — since WireGuard operates over UDP.

NAT traversal and P2P communication isn't new. Even if you're not technical, you're probably using P2P communication daily. When you use Zoom or any other video conferencing software, your video and audio feeds are most likely transferred directly to your counterparty through a P2P channel. This technology is called WebRTC. In this specific case, we didn't want to reinvent the wheel — our idea was to combine it with WireGuard.

WebRTC is a solid protocol with a bunch of RFCs, but we didn't want to implement it from scratch. There's a brilliant open source project called Pion that implements the WebRTC protocol. The full protocol includes encryption (DTLS), which in our case was already handled by WireGuard. Doing double encryption would hurt performance. We dug deeper and decided to use one crucial part of WebRTC: ICE (Interactive Connectivity Establishment), which is used to establish P2P connections. This protocol now lies at the core of NetBird — when two machines need to connect, they trigger ICE to discover the shortest path, and once found, NetBird rolls a WireGuard tunnel over this connection.

Mission accomplished. The connection is direct, P2P encrypted, and very privacy-friendly — nobody beside the user can see or even touch the traffic.

The Viral Takeoff

Now it was time to put hardware and software together and bring it to market. How would anyone approach this? Google Ads? No, Reddit. Overnight, we saw a wave of attention — Reddit threads exploding, screenshots being shared, video reviews popping up. Jeff Geerling even dedicated a full video to it on YouTube that racked up over 700k views.

For a moment, it felt like this little apartment project might actually turn into something big. But then came 2021 — the pandemic year. The chip shortage hit like a brick wall. It became nearly impossible to source the components we needed. The crowdfunding campaign just… stalled before it ever had a chance.

It was the first hint that this idea might need a totally different path forward.

The Pivot

Maycon and I spent a long afternoon debating what we should actually do with this. Somewhere between the whiteboard scribbles and yet another cup of coffee, a different idea emerged — one that, surprisingly, didn't involve hardware at all.

If our peer-to-peer network could power access to home storage, why couldn't it power something bigger? Something that would save platform engineers and network admins an absurd amount of time? What if we built a zero-configuration peer-to-peer network — one that "just works" out of the box, no open ports or firewall configurations required? At the time, WireGuard had everyone's attention, so the timing felt right.

That's when the whole project shifted. It stopped feeling like a weekend experiment and started looking like a real opportunity — something that could fundamentally change how teams connect and operate their infrastructure.

We sat down and just started coding, building a prototype that would connect multiple machines into one mesh network. The networking foundation we'd built for the NAS was more than enough to create an MVP quickly.

When the first network packet sent from my machine reached Maycon's, we thought: "Okay, now we need to show off." How do you show off when you're a software engineer? You publish your work on GitHub.

The Second Viral Takeoff

Publishing on GitHub is not enough — or for that matter, just building something useful is not enough. You need to bring it to people. Luckily, we already had a template for that. Reddit was the place to go. Back in May 2021, I did a little research on which subreddits would be best for such a project. r/selfhosted and r/opensource stood out and seemed like good places to post about what we'd built. So I posted and… nothing!

That was disappointing. We expected similar results to what we'd experienced with the RPi NAS. Well, in programming you use a pattern — with backoff, of course — so we posted again the week after. Same result. For the sake of completeness, we posted a 3rd time (sorry r/selfhosted for the spam). But this time we did some analysis and discovered that on Wednesdays around 6–7pm, there's always peak activity. And it worked! Maycon texted me: "GitHub stars are exploding." As if I wasn't already sitting in front of my laptop refreshing the GitHub page xD.

As a software engineer, I've always been fascinated by projects with more than 1,000 GitHub stars. Whenever I'd see one, I'd think: wow, these guys rock. It became my personal benchmark for choosing open source software — if it has over 1k stars, it's probably solid.

It took us just a couple of days to hit 1,000 stars, and it felt like we were gods. But Maycon kept us grounded: "I wouldn't run this in production yet." Neither would I — I failed my own benchmark xD.

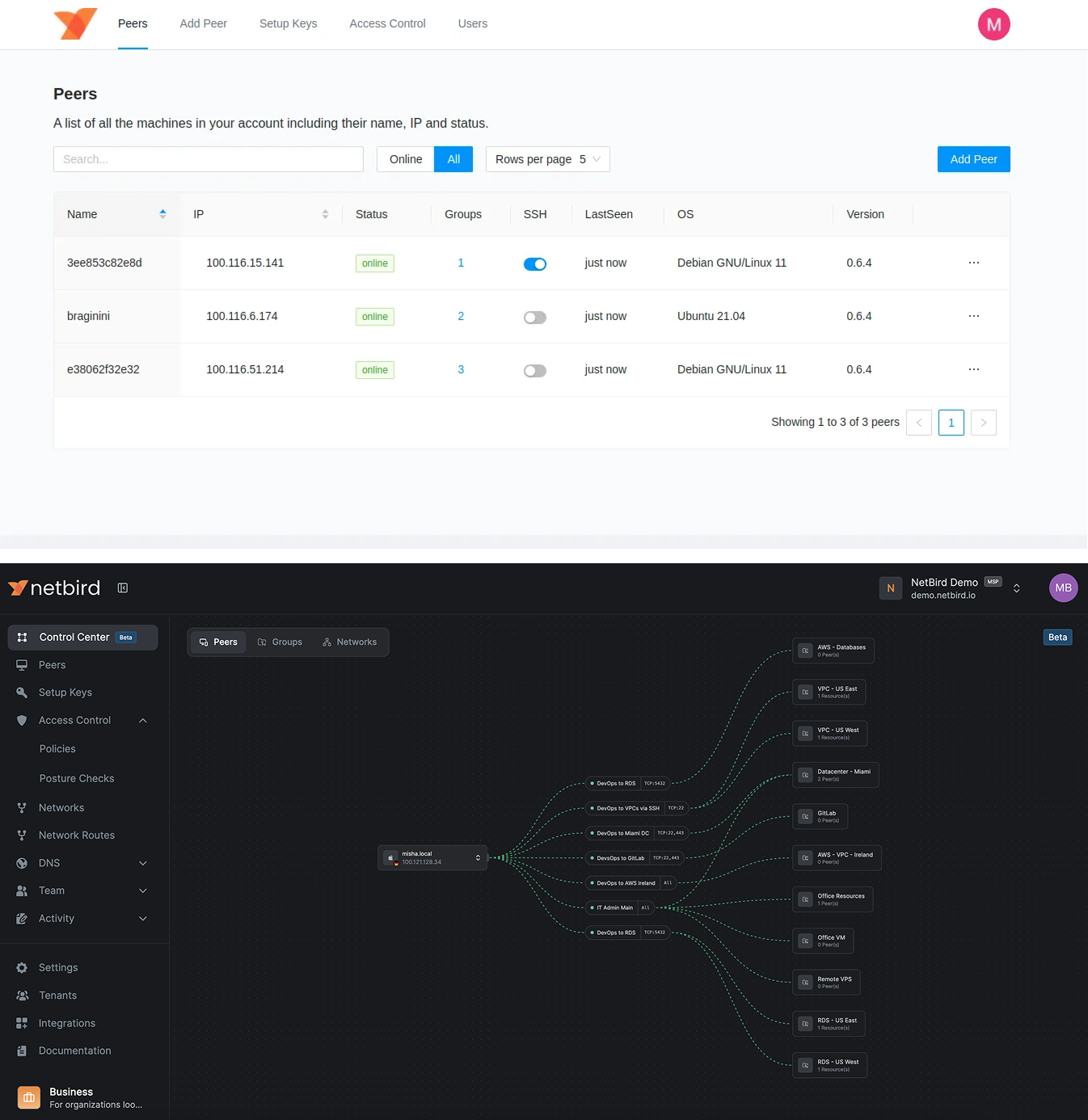

Today? Absolutely. Back then, we still had work to do. Just look at how far we've come:

The Fast, The Secure, The Reliable

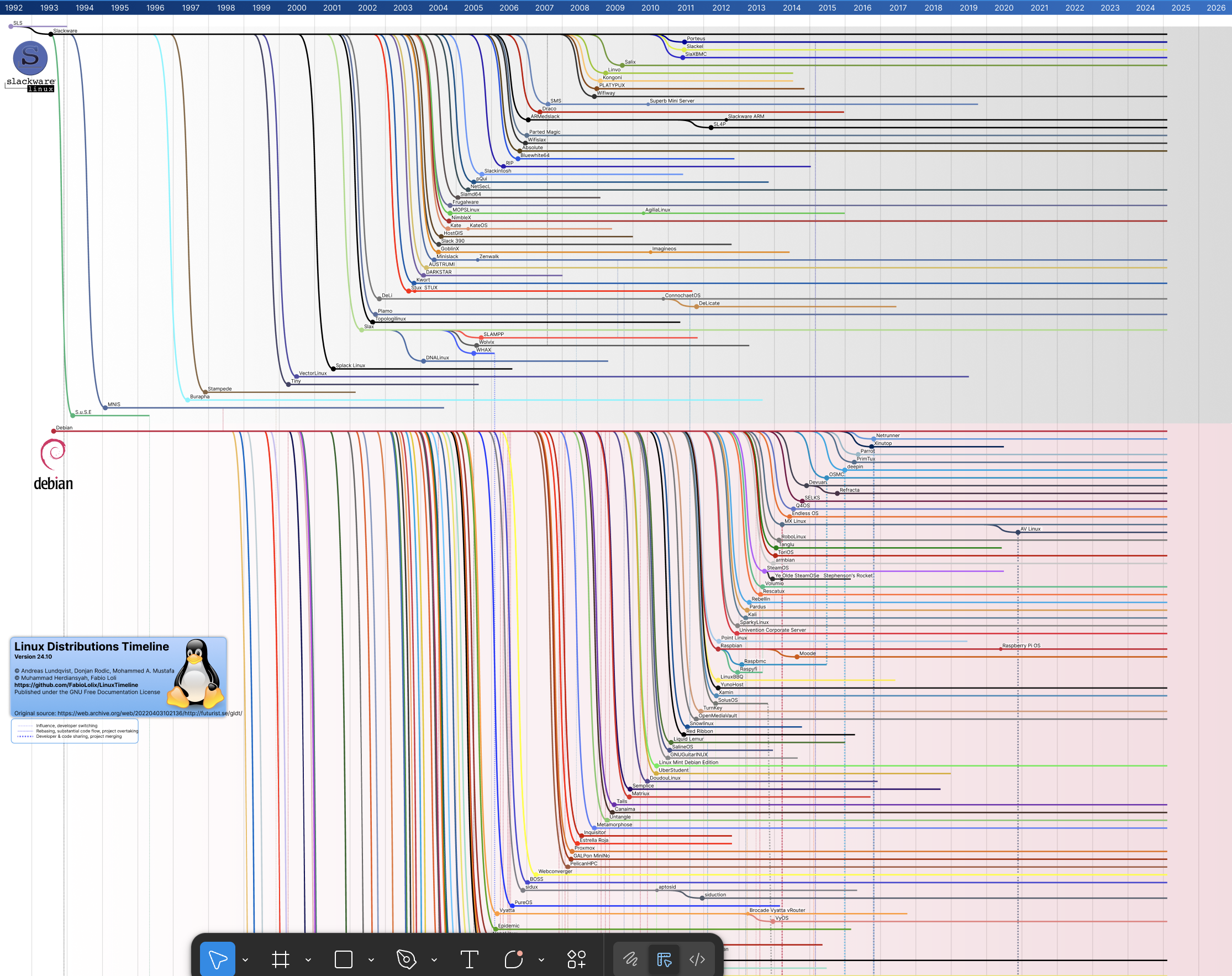

Here's the thing: networking is complex — not something you can vibecode overnight. The number of operating systems and network environments to support is just insane. Do you know what this picture represents?

That's a Linux distribution tree, and people actually run these systems in production. On top of that, network admins love to tweak settings in ways you'd never expect, and all of that combined makes it incredibly hard to build something that works everywhere.

There's another point worth mentioning: when running networks in production, you need to trust a solution. In network security, trust is earned over time.

The networking layer must be fast, secure, and reliable. So we had a lot of work ahead of us — and we were fine with that. We committed to building an advanced networking platform that's both easy to use and affordable for teams of all sizes. By going open source and staying close to the community, we aimed to set the industry standard for connecting and securing IT infrastructure.

The 5% Deal

So here we are.

NetBird started as a side project in an apartment — no pitch deck, no roadmap, and honestly no real plan beyond "let's just do it and see if it works."

It turned into hardware. Then into networking software. Then into an open source project that people actually love. And eventually, into a company with a small but very focused team of brilliant engineers.

Today is January 2026. We've raised a Series A. Not because we woke up one day and decided we wanted to "raise a round," but because the problem we were solving kept growing. At some point, it became clear that a few people and a GitHub repo were no longer enough to do it properly. We're building something that has to work everywhere — not just in ideal conditions.

Every operating system. Every kind of network. Every corporate firewall. Every "this setup makes no sense, but somehow it's running in production" environment.

That kind of software doesn't come from vibe coding over a weekend.

It comes from engineers who care deeply about correctness, performance, and reliability — even when nobody is watching. People who don't mind reading RFCs on a Sunday afternoon. People who get uncomfortable when abstractions leak, and quietly go fix them. People who feel an unreasonable amount of satisfaction when a packet finally takes the right path.

Which brings me back to the line at the very top.

"If you can vibecode NetBird in a weekend, you get 5% of the company."

You can't. And that's exactly the point.

What we're building is genuinely hard — but it's also deeply fun, in the way only hard technical problems can be. It's meaningful work, used by real teams, running in real production environments, where failure actually matters and success is quietly relied on every day.

So here's the real deal. We're looking for exceptional engineers.

Backend, networking, distributed systems, infrastructure, Go, Linux, security — people who enjoy going deep and don't stop at "good enough." People who want real ownership, real responsibility, and real impact on the shape of the system they're building. People who want to ship things, break them carefully, fix them properly, and make them boringly reliable.

If that sounds like you, you should talk to us . If you're just curious, you should probably still talk to us.

And if you simply enjoy reading stories about how real software gets built — thanks for sticking around until the end.